In his new book on post-war European leaders, Tom Gallagher assesses Nicola Sturgeon’s disastrous legacy, and how her failure provides an insight into Europe’s Leadership Famine.

Nicola Sturgeon definitely merits a chapter in a book on European leadership. It isn’t because she left Scotland a better place than she found it or because under her the independence cause flourished. Neither thing happened. Indeed, many of the 12,000 people who crowded into Scotland’s main events venue, the Hydro in Glasgow on 22 November 2014 to hail her emergence as First Minister of devolved Scotland and leader of the Scottish National Party (SNP) would today bitterly assail her as a fraud who had duped them.

Her low standing in the pantheon of Scottish Nationalism is shown by the fact that the family of the recently deceased, Winifred Ewing the architect of the nationalist breakthrough in Scotland, have delivered a pointed snub to her. Instead of being asked to deliver a tribute at her memorial service in Inverness Cathedral later this month, the honour goes instead to two of her fiercest detractors in the increasingly divided independence movement, Alex Salmond and Alex Neil.

Mrs Ewing is famous for having said ‘Stop the world, Scotland wants to get on’. Arguably, under Sturgeon a furious effort was made to locate Scotland in the fractious and weird world of left-wing student union politics.

She turned her cause into a vanguard movement ready to embrace increasingly unconventional ideas for re-engineering humanity, or at least the portion calling itself Scottish. She was outspoken about the desirability of wishing to repudiate existing identities based on the nuclear family, nation, or class in favour of ones advanced by those who presume to speak for submerged and oppressed minorities.

But her ambition was greater than her reach. She was an unoriginal thinker who relied on a small army of spin doctors to carve out an image as a semi-Renaissance figure absorbed by books, theatre and a medley of contemporary ideas. She micro-managed areas of government that she felt could strengthen her profile but accumulating problems, ranging from an ailing health service, mounting drug deaths, costly procurement failures, and underperforming schools, blighted her eight years running Scotland’s internal affairs.

Looking back, it is still remarkable to observe how she ensured that her party just became an appendage to her rule. It was no mean feat to accomplish that and it has left scars that may be impossible to heal. She sought validation from global forces using wealth and power in a bid to socially re-engineer humanity. This meant noisily jumping on various fashionable bandwagons.

She and her party thrived thanks to the arrival of social media which admired edgy radical causes. Her rise and fall saw her sharing major decision-making roles with Alex Salmond up to the 2014 independence role, to her succession I 2014, followed by a barely-concealed attempt to liquidate him politically in what proved a messily brutal but unsuccessful operation.

Seen in European terms, it is remarkable that she hung on for so long, given her absence of political realism, her unwillingness to compromise and her lack of respect for governing expertise. Her propaganda service extolled her as a European leader but, in reality, it is hard to find another European leader as visible as her who was so lacking in elementary leadership skills.

In France, Italy, Greece and the Netherlands, parties that were once household names have died or nearly vanished after many years at the top. Radical alternatives wait in the wings (or have already taken over as in Italy) while saviours with Sturgeon’s ambition and lack of reach, like Macron, struggle to avoid being swept away.

It will take some time to assess the true significance of a ruthless, dour and abrasive leader like Sturgeon. But some things are already obvious.

She was the beneficiary of the mistakes and over-reach of the SNP’s chief opponents. The growing professionalism of the SNP enabled these altered political conditions to be turned to its advantage. Despite regular descents on European capitals during the Brexit years, it wasn’t the cause of European integration but political events in London that absorbed Sturgeon’s attention. Under her, the SNP with its emphasis on personality and its absorption with presentation and expanding its influence across state and society, increasingly came to be a north British version of New Labour rather than a fresh Scottish political force.

Sturgeon sought legitimacy in ways that had been tried out by rulers in London with distinctly mixed results. Like Labour she sought to build an appealing brand by reaching out to figures in the entertainment fields and cultivated business types, but only for most to grow wary about her intentions. The state was also expanded into areas of public life where neutrality once reigned.

Just like Labour she was unable to devise an alternative project, one that, in her case, would differentiate Scotland from developments in the rest of Britain. She left the mainly working-class voters, who had given the SNP big majorities in 2011 and 2015, far behind. The disenchanted post-industrial Scots with poor health standards and economic prospects, remained deprived and overlooked. Like Labour under Blair, her rule was increasingly middle-class in focus. The lifestyles, and habits of ordinary Scots (especially the younger ones) were increasingly managed and policed by an interventionist state.

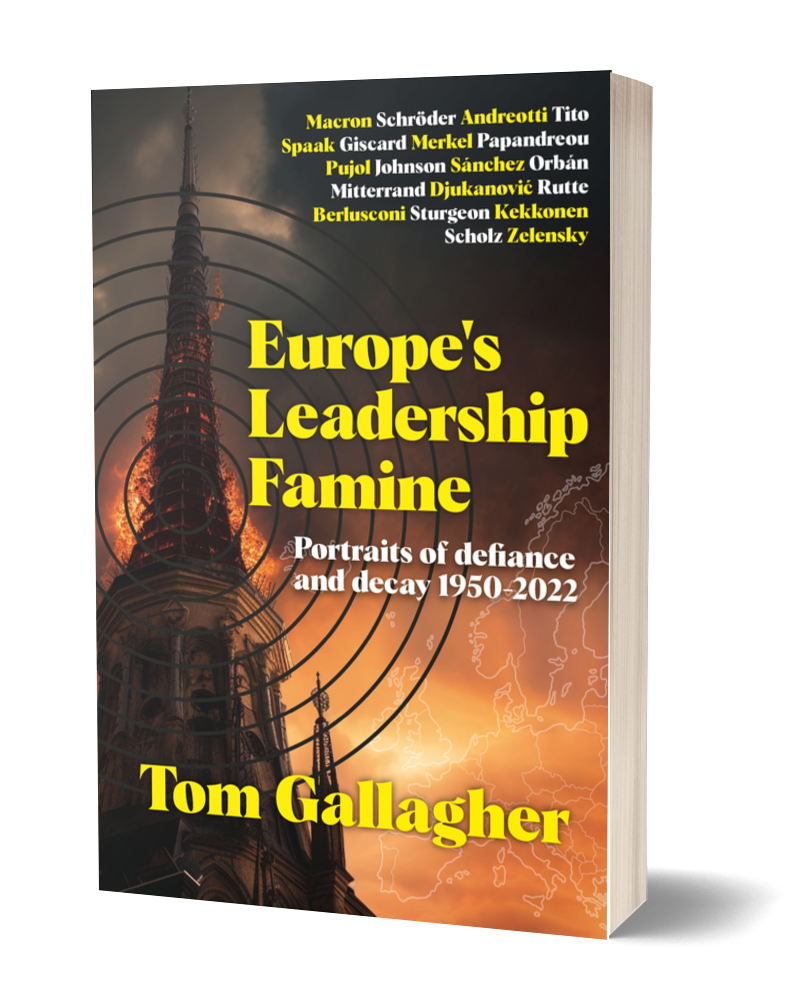

Europe’s Leadership Famine

Tom Gallagher’s new book examines the careers, formative experiences, outlooks and intentions of twenty European leaders, from Tito to Macron, from Sturgeon to Zelensky, in five thematic sections, from The Cold War through identity politics and renewed war in Europe. Most of these leaders left their countries weaker. A small number at times sought to defy networks of power or patterns of thought that diminished Europe and corroded democracy.

How can Europe remain mostly free and adequately governed, if this leadership famine drags on?

She eagerly adopted Green transport and industrial and health restrictions that, as during the pandemic, seemed designed to crush the autonomy of citizens. In the process her party ceased to count.

Sturgeon was listless about using years of turmoil and gridlock at Westminster to try and bring independence nearer. The campaigns upon which she lavished her time, state resources and large amounts of legislation, were fashionable ones imported from West Coast America or London. The Me Too movement, urban-inspired Green causes, the pro-EU Remain cause and latterly gender ideology enabled her to latch on to counter-culture icons like Greta Thunberg.

Despite running a tightly centralised administration, she argued that she was taking on oppressive forces of authority that stood in the way of a progressive transformation that young people in particular could benefit from. But her 2022 Gender Recognition Reform bill, whose aim was to allow persons as young as sixteen to alter their gender without the need for a medical diagnosis, was viewed as a grave setback for womens’ rights and sparked turmoil in her party and in Scottish society, contributing to her downfall.

Critics argued that by promoting fashionable causes approved by the media and corporate moguls, she was essentially promoting herself and badly damaging the SNP’s independence cause. Her dogmatism in pursuing some of the most controversial features of this progressive agenda reflected the tenor of much of the discussion about the contemporary world in academia and the media. But she was not operating in a university sociology department or a sprawling human resources office. Ultimately, she had to persuade rather than browbeat public opinion.

She was simply too unsubtle and intimidating at times to be an effective recruiter for the various new dogmas for post-modern living. She had already shown herself to be too blinkered and short-term in the way she approached the eternal struggle to prise yet more political power from London.

Sturgeon seemed to be a forerunner of the type of politician preferred by the World Economic Forum or the Soros Foundation if carefully elected Citizens Assemblies rather than elections determined who ought to be the rulers.

She is now likely to concentrate on forays into biography. But the portraits that will prove durable are likely to be the ones that shed light on the personal and psychological conflicts that made her an exacting colleague and a leader avid to disrupt rather than improve society.

Hubristic politicians obsessed with their own personal destiny, and who sometimes view humanity itself as an onerous burden and an obstacle to progress, are increasingly noticeable in different parts of the English-speaking world. Scotland has little to congratulate itself about so far this century. But it should take a bow for casting into the political wilderness someone as ill-equipped to be a democratic leader as Nicola Sturgeon.

Tom Gallagher is a Scot who pursued an academic career as a historian in England for over three decades and is currently Emeritus Professor of Politics at the University of Bradford. His latest book, Europe’s Leadership Famine, published by scotviewbooks, is now available on Amazon.

Help The Majority fight for you

Help us amplify your voice with a monthly or one-time donation. Everything, big or small, is appreciated. Thank you for your support!